Between 2020 and 2022 I was an Artist Research Fellow at the Hispanic Society of Americas, where I studied works related to the language and aesthetics of colonization and imperialism.

This fellowship heightened my historical perspective of cultural prevalence, broadening my horizons and substantiating several of my initial interpretations. From the very beginning, I felt quite intrigued by the institution’s mission statement:

“The mission of The Hispanic Society of America is to collect, preserve, study, exhibit, stimulate appreciation for, and advance knowledge of, works directly related to the arts, literature, and history of the countries wherein Spanish and Portuguese are or have been predominant spoken languages.”

As a visual artist interested in the misrepresentations of language, it was then with a great sense of wonder that I contemplated such interesting parameters: not geographic boundaries or a particular medium, but the spoken languages from the Iberian Peninsula which, by violent means, were spread throughout the world.

My amazement just kept growing once I began to delve into the Library. Maps, manuscripts, letters and documents dating from the 11th century to the present, and more that 300.000 books and periodicals from places whose cultures were oceans apart, all collected as result of a single common denominator: the language of the colonizer. This curatorial cut and its inherent contradictions are of particular interest to me as a Brazilian, for the brand of Portuguese we speak in my birthplace, Bahia, contains a vast quantity of words and idioms from both the local indigenous cultures and the African languages that were brought in as result of the slave trade.

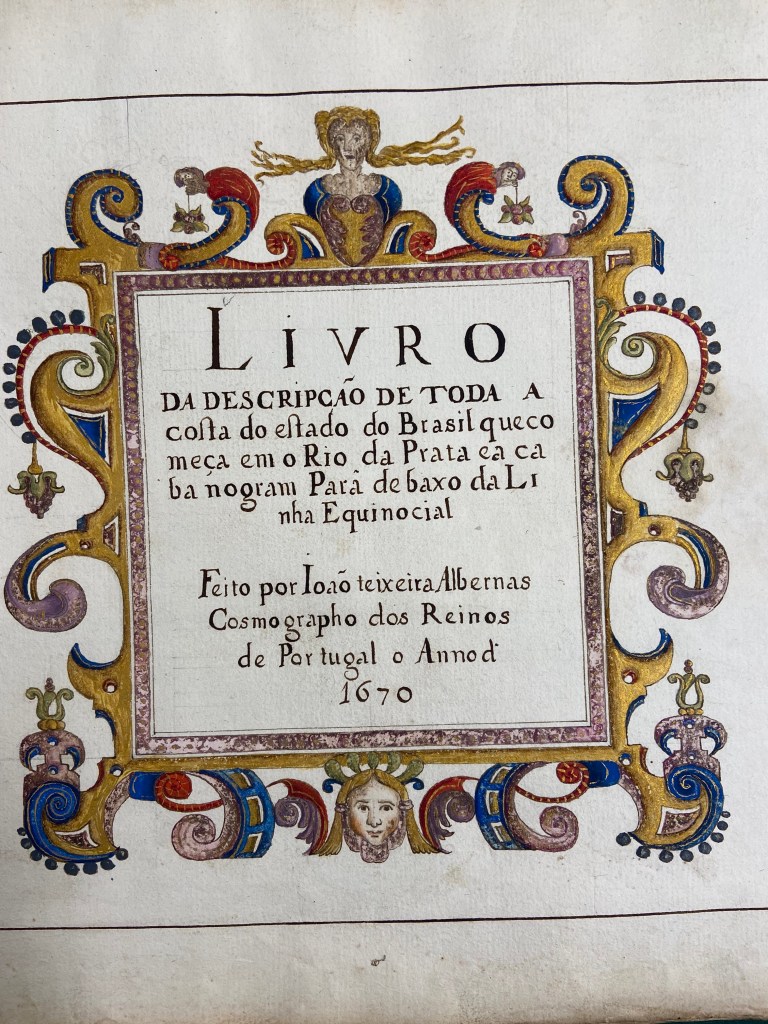

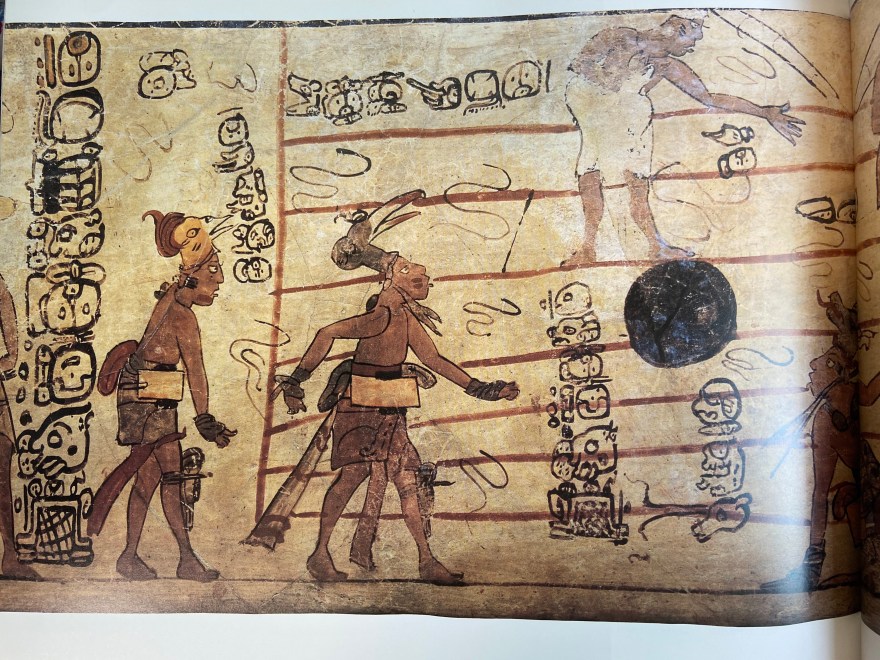

I studied some of the first maps made of the Brazilian coastline, and observed how some locations kept their original pagan names, while others – the main ports and bays – were from the beginning baptized with Christian names. The collection also features many objects bearing the Mayan hieroglyphs, fascinating examples of language as visual element. Also present is an abundance of biased interpretations of indigenous names for places and forces of nature, as well as their myths and social structures.

With all of that in mind, I began to conceive of a body of work based on the idea of a reverse route for the historical documents and works of art collected at Hispanic Society of Americas: a fictionalized, abstract version of what would those look like if nations from the New World had gone to Europe before the colonizers took over. For instance, maps. As I mentioned earlier, I spent a great deal of time with materials about the coast of Brazil in the 1600s, looking at the proportion of geographic names that had been kept in the indigenous language versus the names of places that were christianized. How would a version of the coast line of Portugal look like if it had been charted by a person of Tupi-Guarani ancestry? Which places would have kept their original names, and which places would be renamed in ways that were meaningful to the Tupi-Guarani culture?

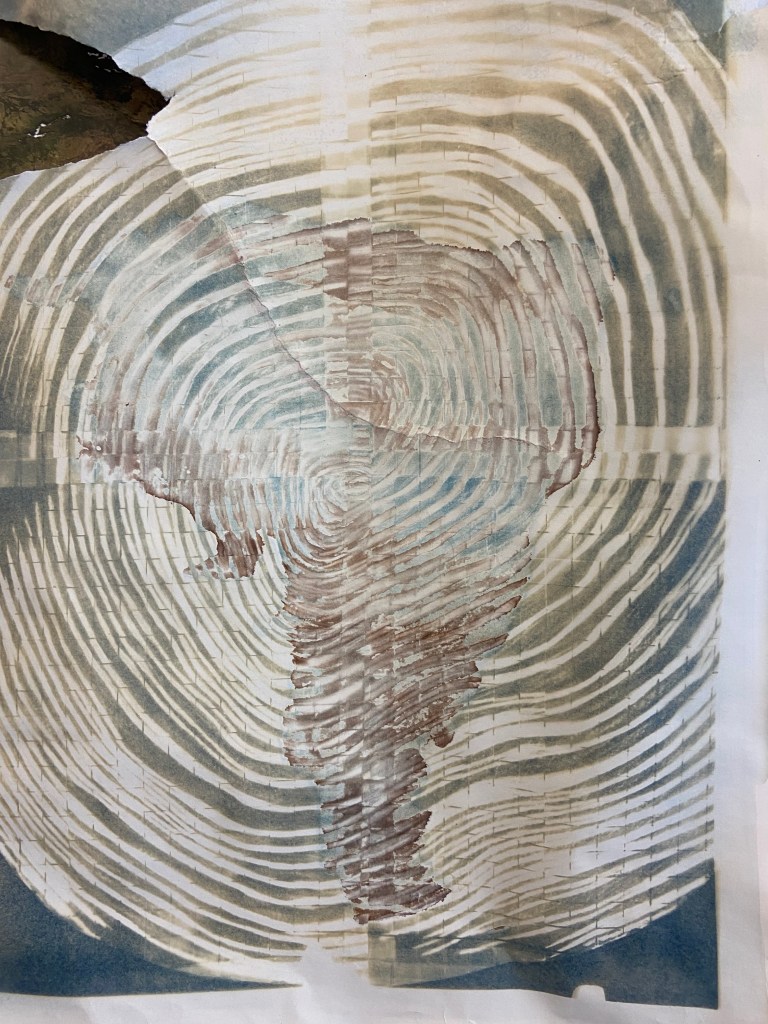

On the summer of 2023, I had the great fortune to be part of an LMCC residency cohort at the Arts Center in Governor’s Island. It was a summer of commuting by boat, under skies made orange by the ashes from wild fires blazing in Canada. Meditating upon the technologies available to our pre-Colombian ancestors, I began to weave transparencies, and to experiment with alternative photo-processes.

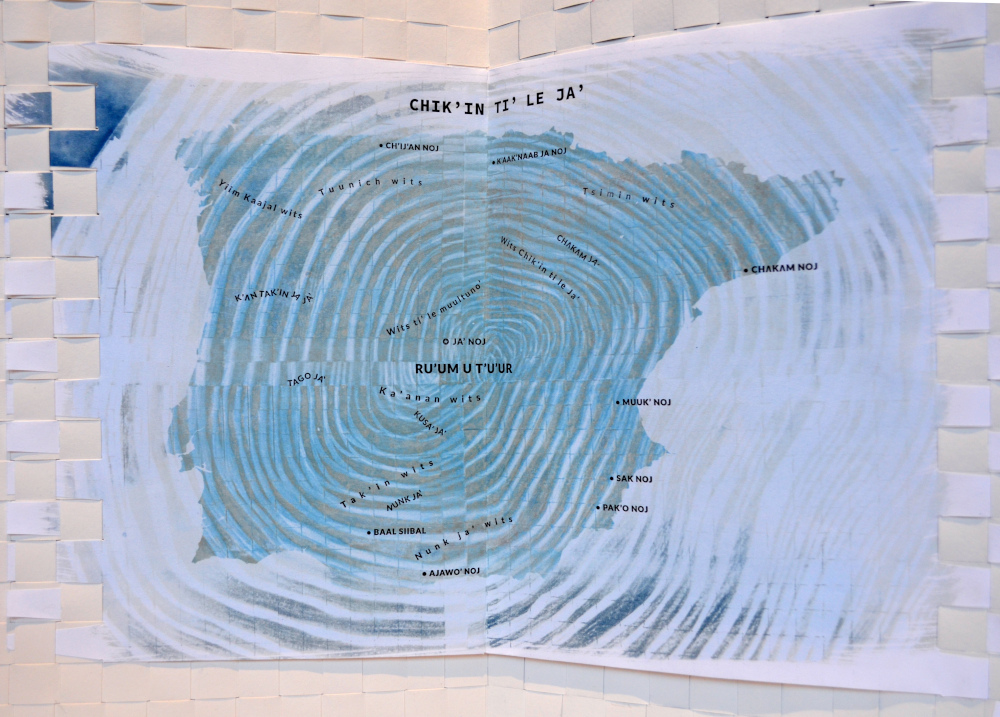

Atlas Inverso is the culmination of all those years. Three collaborators – Sofi Lopez Arredondo, Erny Ros Valeros Manlangit, and Wakay – were invited to consider the main geographic features of Portugal and Spain according to Mayan, Tagalog, and Tupi-Guarani ethnologies, underscoring language’s role in cultural preservation.

The Atlas also features contour maps of Central America, the Philippines, and South America as artistic renderings of the dramatic consequences of long-distance navigation for the original inhabitants of these places, accompanied by observations taken during the research fellowship period in the form of journal entries and notes exchanged between the collaborators.

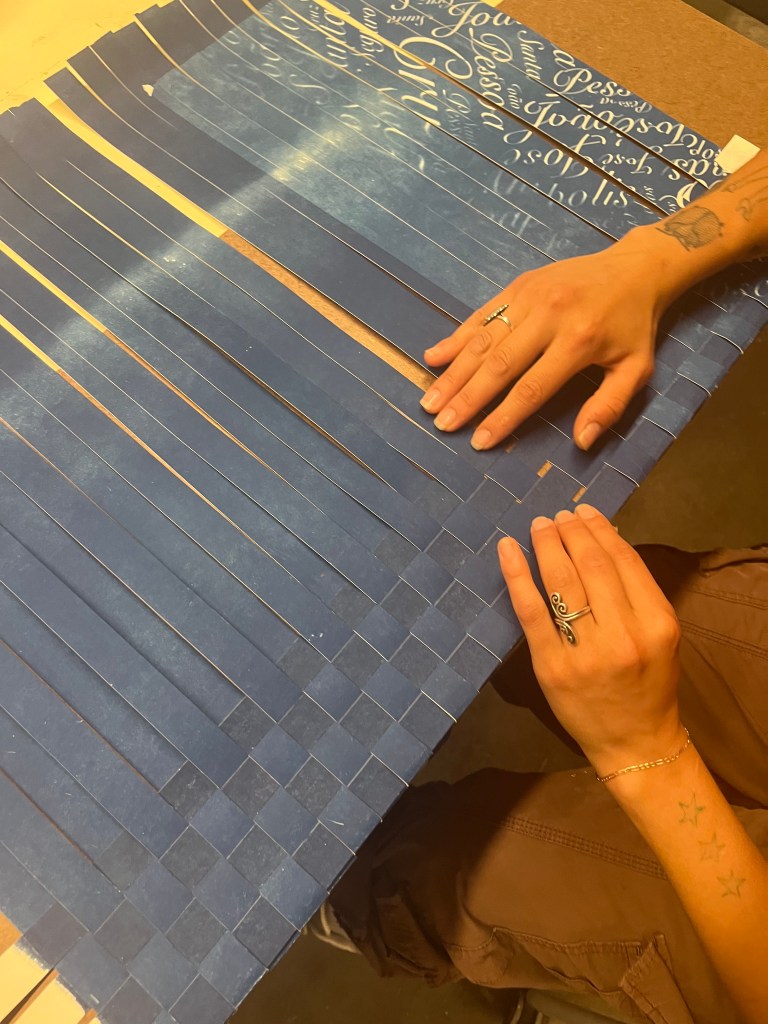

Also included are charts displaying the translations to English for all the substituted names and their meanings. The pages of this atlas were created entirely using the same weaving technology employed by indigenous cultures to produce household objects, resulting in a two-sided 15-foot-long mat (when completely open).

In 2024 I became a member at Shoestring Press, an awesome (and I rarely use this word) printshop in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. It was there that I editioned the images–my second summer laboring on this project. After the alternative photo-processes were done, I took the images to Tor View Press, upstate New York, for the letterpress layer of printing. The Tor View Press is the home of poet/artist KS Lack, one of my dearest friends—really a sister, so working there is very much like coming home.

I am now at the stage of weaving the 15ft-long mats where the images get attached. It takes a solid 40 hours of weaving per book and it is an edition of nine copies, but again I am a lucky gal: first i got a ton of help from Jess Russ and Thomas Gallagher, then the weavers extraordinaire Cole Javis Sativa and Lucia Van Ryzin came aboard to help me produce the first four copies. The other five will be the product of yet another summer, aiming to be all done this year.

Wish me luck.